A Legal Guide to Discussing the Weather (UK Edition)

How Small Talk Becomes a Liability

There was a time when discussing the weather in Britain was not merely safe, but civic—a low-stakes ritual of shared reality. It required no preparation, no courage, and very little thought. It was the conversational equivalent of a nod: a neutral acknowledgement of shared existence. That time has passed.

Weather has become a proxy topic, and proxy topics carry risk. What was once small talk is now adjacent to policy, economics, public health, climate strategy, regional equity, and personal responsibility. The weather no longer describes conditions; it implies positions. Accordingly, some guidance is now required.

At first glance, “it’s cold” appears to be a factual statement. In practice, it is rarely received as such. Depending on context, tone, and audience, the phrase may be interpreted as a criticism of energy policy, an implicit comment on heating affordability, a political observation about fuel poverty, a coded grievance regarding sanctions, or—most dangerously—a failure to acknowledge climate resilience. Adding “for this time of year” significantly increases exposure. Historical comparison introduces memory. Memory suggests expectation. Expectation implies entitlement. Entitlement should be avoided.

Describing a day as “lovely” introduces unnecessary certainty. It may not be lovely for those working outdoors. It may not be lovely for those experiencing seasonal affective disorder. It may not be lovely in other parts of the country. It may not be lovely in the future. Certainty creates exclusion. Exclusion creates risk. Positive affect is no longer neutral. Where appreciation is unavoidable, moderation is advised.

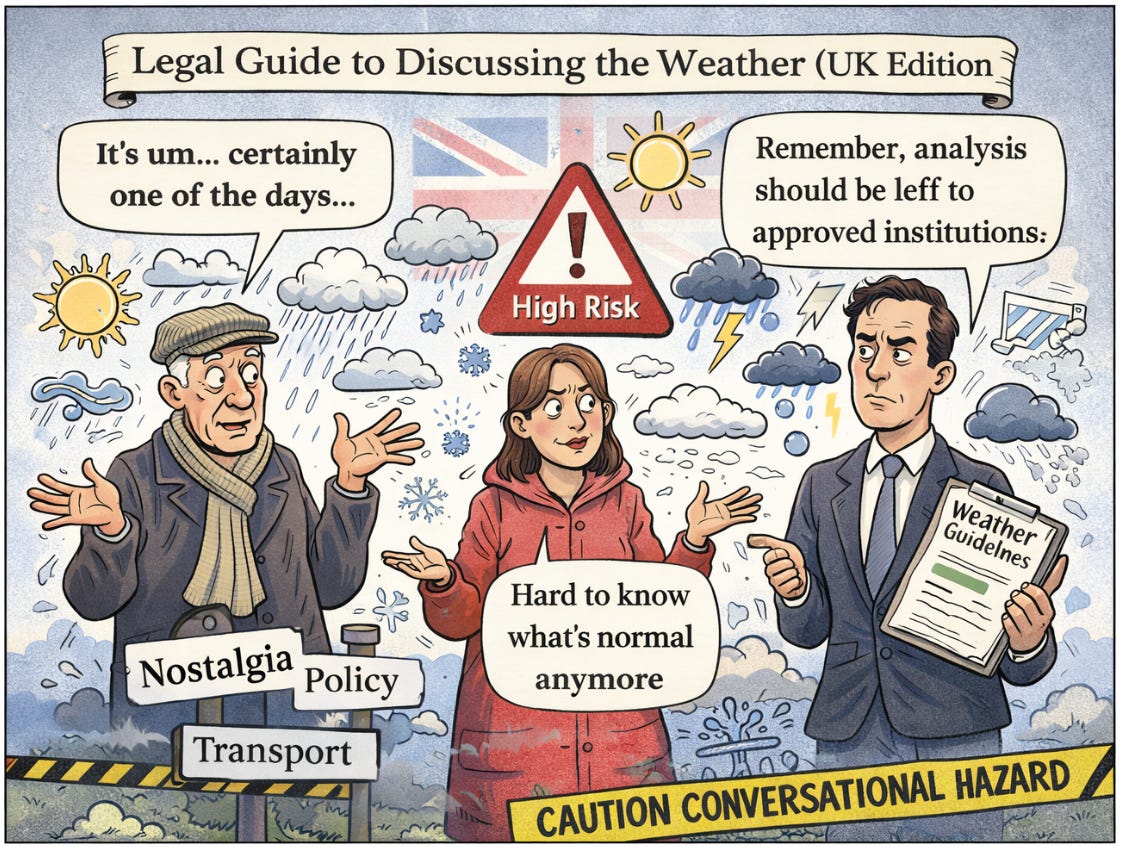

Some weather remarks appear observational but carry analytical weight. Statements such as “winters don’t feel the same anymore,” “summers seem hotter,” or “we used to get more snow” imply memory, comparison, and pattern recognition. Pattern recognition suggests analysis. Analysis should be left to approved institutions.

Rain presents particular challenges. Complaining about rain may be interpreted as negativity. Enjoying rain may be interpreted as insensitivity to flooding victims. Failing to mention rain during rain may be interpreted as avoidance. The recommended approach is measured acknowledgement without conclusion. For example: “Yes, there does appear to be some precipitation.” No follow-up is advised.

Weather rarely remains contained once introduced. It has a tendency to drift toward transport complaints, cost-of-living remarks, infrastructure observations, or nostalgic references to how things used to be. This process, known as conversational drift, should be anticipated and pre-empted. If weather discussion exceeds twenty seconds, a polite exit is recommended.

Statements comparing regional weather conditions—such as “it’s always raining here,” “it’s nicer down south,” or “up north it’s colder”—may create geographic tension. Britain experiences weather collectively. Individual impressions are best kept internal.

The following phrases have been found to carry minimal risk: “Yes, it’s certainly one of the days.” “Hard to know what’s normal anymore.” “The weather’s doing its thing.” “It is what it is.” Avoid elaboration.

Weather remains a viable conversational tool provided it is brief, non-judgemental, ahistorical, and emotionally neutral. If the urge to comment persists, citizens may instead acknowledge the existence of weather silently. This approach avoids misinterpretation while preserving social harmony. In most cases, it is sufficient.