An Explanation of Natural Law

Most of what passes for “law” in the modern world is not law at all. It is permission. It is authority asserting itself through rules that change with power, fashion, or expedience. Natural law is something entirely different. It does not depend on courts, governments, or enforcement. It does not need belief. It operates whether acknowledged or denied, just as gravity, seasons, or biological limits operate regardless of opinion.

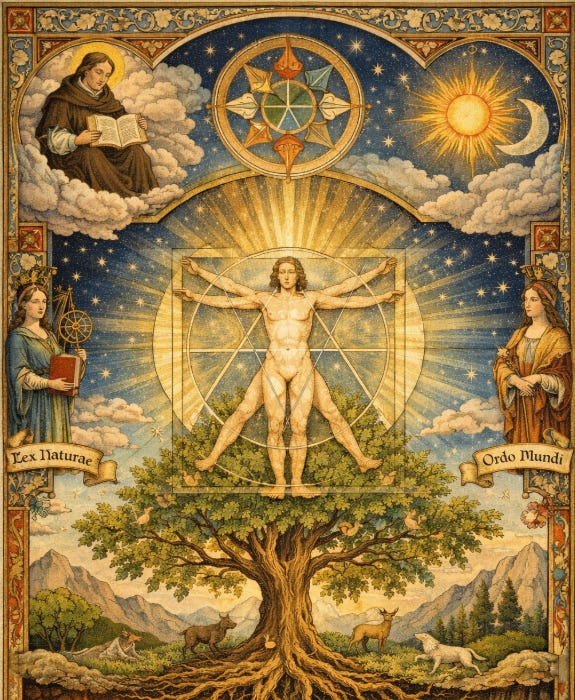

Natural law is not a religious doctrine, though many traditions have attempted to describe it. Nor is it merely moral sentiment. It is structural. It is the underlying order that governs what can exist, what can endure, and what inevitably collapses. Where positive law is written by men, natural law is discovered through reality itself. It is not imposed; it is revealed.

This distinction is ancient. Aristotle observed that there is a form of justice that exists “by nature” and not merely by convention, something that remains valid regardless of what any city happens to legislate. The Stoics argued that reason itself participates in a universal order—that there is a rational structure to reality which human law can either reflect or violate. Cicero gave this its clearest expression: true law is right reason in agreement with nature, unchanging and eternal, binding on all people and all times. No senate, no ruler, no decree could annul it.

The medieval world did not invent this idea; it systematized it. Thomas Aquinas described natural law as the participation of human reason in the eternal law—the rational order by which reality itself is governed. For Aquinas, human laws were legitimate only insofar as they reflected that deeper structure. A statute that contradicted natural law was not merely unjust; it was, in a meaningful sense, not law at all.

Early modern thinkers carried the same insight into political theory. Hugo Grotius argued that natural law would remain valid even if, hypothetically, God did not exist—because it arises from the rational and social nature of human beings themselves. John Locke grounded rights not in government grants but in the pre-political structure of reality: life, liberty, and property were not permissions from the state but conditions that law was meant to recognize and protect. Even the American founding, however imperfectly realized, was explicitly framed in these terms: rights were said to be “self-evident,” not manufactured by authority.

What all of these thinkers shared was a simple but radical premise: law is not whatever power declares. It is whatever aligns with the structure of reality and the requirements of human flourishing. Legality and lawfulness are not the same thing. A command can be legal while violating the deeper conditions that allow human beings and societies to remain whole.

Modernity quietly abandoned this idea. Law came to be understood increasingly in positivist terms: whatever is enacted by recognized authority is law, full stop. Questions of justice, truth, or coherence were relegated to politics, ethics, or opinion. This shift replaced an external standard—alignment with reality—with an internal one—procedural validity. If the rule was passed correctly, enforced effectively, and recognized institutionally, it was deemed lawful, regardless of whether it reflected anything true, just, or sustainable.

The consequences of that shift are not abstract. They are visible everywhere. Financial systems legally constructed around abstraction rather than real value become unstable. Political systems legally authorized yet structurally dishonest become incoherent. Social systems legally permitted to extract without reciprocity eventually erode the very conditions that allow them to function. None of this requires moral condemnation. It follows from structure.

This is the core of natural law: reality has rules that cannot be broken without consequence. A structure that violates load-bearing principles will fall. A body that violates biological limits will fail. A society that violates the requirements of truth, coherence, and reciprocity will fracture. These outcomes are not punishments. They are the natural result of misalignment with how the world is actually organized.

At the most basic biological level, this is already obvious. A mother will protect her child. Not because a statute instructs her to do so, and not because a social contract requires it, but because the structure of life itself demands it. The survival of offspring is embedded in the biology of mammals. Any system—legal, political, or cultural—that attempts to override that bond does not become “progressive.” It becomes unstable. It is working against the grain of reality.

The same principle appears in another form across the living world. Any being will defend its home. A bird guards its nest. A fox its den. A person their dwelling. Territory is not merely habit or tradition; it is the spatial condition of survival. Shelter, boundary, and belonging are biologically rooted. Systems that deny this—by treating place as disposable, by severing people from land, home, or continuity—do not produce freedom. They produce disorientation, dependency, and conflict. What appears as instinct is in fact structural law expressed through life.

The principle does not stop at territory or reproduction. It applies wherever reality has determinate structure. Pretending that biological sex does not exist does not make it so. Human beings are sexually dimorphic organisms. That fact is written into chromosomes, reproductive anatomy, developmental pathways, and evolutionary function. One may adopt social roles, identities, or expressions, but the underlying structure remains what it is. Systems that insist otherwise are not expanding reality; they are attempting to legislate it out of existence. As with any other denial of structure, the result is not liberation but confusion, instability, and the need for increasing coercion to maintain the fiction.

It is important to distinguish this from questions of attraction or relationship. Biological sex is a structural property of the organism. Sexual orientation concerns relational behavior within that structure. Two men or two women do not cease to be biologically male or female by virtue of whom they love. Homosexuality does not attempt to redefine the architecture of the body, the nature of reproduction, or the material basis of sex. It exists within biological reality rather than denying it. Natural law describes what is structurally real; it does not require that every human relationship conform to a single biological function. Where instability arises is not from difference in orientation, but from systems that demand the underlying structure itself be treated as fictional.

This is why natural law is not about what one “ought” to do in a sentimental sense. It is about what is structurally sustainable. Truth matters not because it is virtuous, but because systems built on falsehood cannot remain stable. Coherence matters not because it feels noble, but because contradiction produces internal instability. Reciprocity matters not because it is polite, but because extraction without replenishment destroys the substrate on which any system depends.

Even modern science, stripped of metaphysics, still assumes what natural law thinkers always insisted: that reality is ordered, intelligible, and governed by discoverable constraints. Physics does not negotiate with opinion. Biology does not bend to ideology. Information does not reward contradiction. In this sense, natural law never disappeared. It was simply confined to the physical domain while being denied in the human one.

What makes natural law uncomfortable is that it does not grant exemptions. Institutions cannot vote themselves out of it. Markets cannot arbitrage it away. Technology cannot override it. One can delay consequences, mask them, distribute them, or export them, but one cannot eliminate them. A system that rewards falsehood, fragmentation, or exploitation may persist for a time, but it will increasingly require force, censorship, or illusion to maintain itself. Those are not signs of strength. They are signs of misalignment.

This is also why natural law has always been threatening to empires. Empires rely on control of narrative, currency, and force. Natural law recognizes none of these as ultimate. It does not care who declares value if the structure underneath is hollow. It does not care who claims legitimacy if the system violates the conditions of coherence. In that sense, natural law is the quiet limit placed on every form of domination.

To live in accordance with natural law is not to become “virtuous” in a theatrical way. It is to become structurally aligned. It is to build one’s actions, relationships, and institutions on what is actually sustainable: truth over convenience, coherence over ideology, reciprocity over extraction. This is not utopian. It is practical. It is the difference between something that must constantly be propped up and something that can stand.

The deeper implication is that many of our contemporary crises are not accidental. Financial systems built on abstraction divorced from real value, political systems built on narrative rather than accountability, technological systems built on manipulation rather than understanding, and cultural systems built on fragmentation rather than coherence are not merely flawed. They are misaligned. They are operating against the grain of the structure that governs reality. Their instability is not a bug. It is the signal.

Natural law does not promise comfort. It does not guarantee that alignment will be easy or immediately rewarded. But it does offer something more durable than power: integrity of structure. A world organized around truth, coherence, and reciprocity does not require constant enforcement to exist. It persists because it fits the way reality itself is arranged.

The uncomfortable possibility is this: much of what we are told is “normal” may not be lawful at all. It may be legal, profitable, fashionable, or dominant, but not aligned. And if that is so, then the question is not whether such systems will fall, but when. Natural law does not argue. It does not threaten. It simply outlasts.