Prediction or Plan? Reading The Economist’s 2026 Cover as Signal, Not Forecast

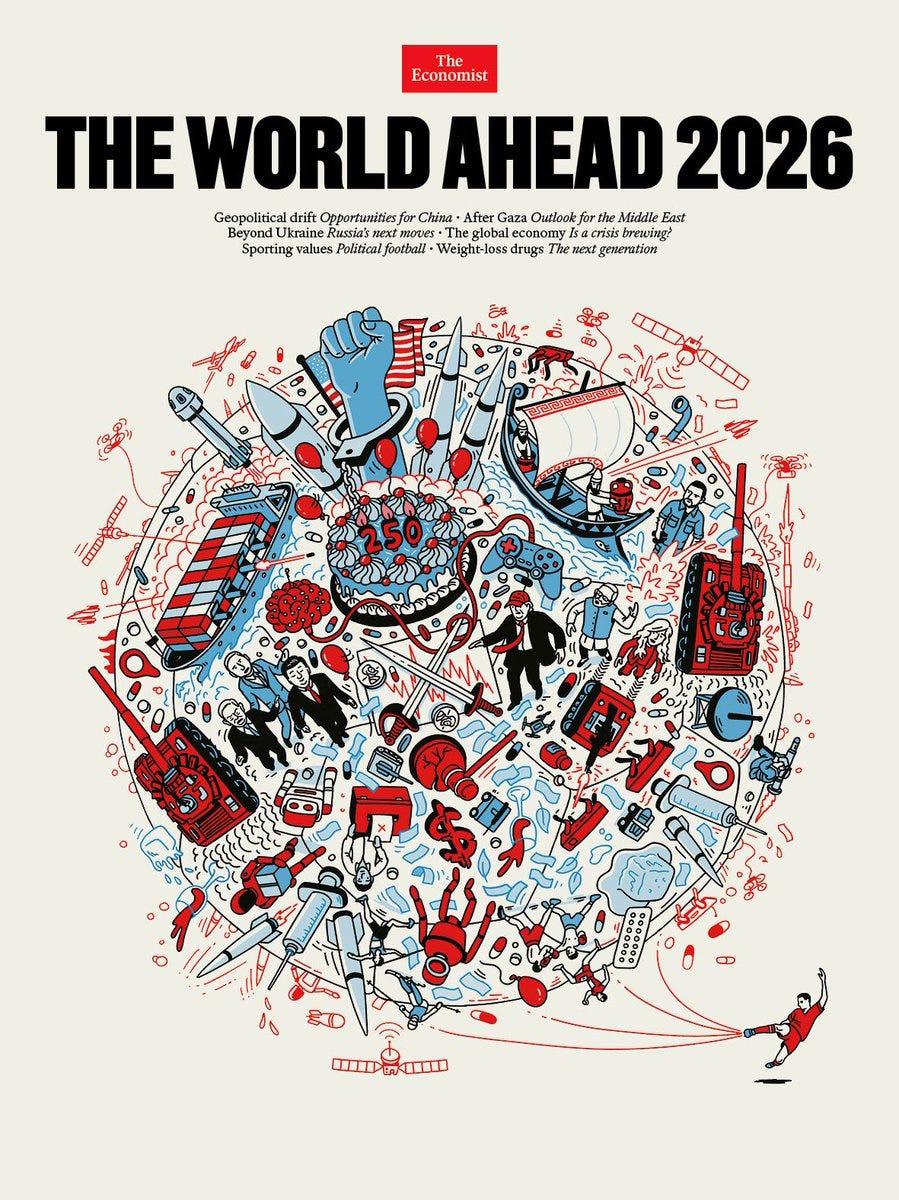

The Economist, “The World Ahead 2026” cover

Every year the “World Ahead” cover arrives with the same promise: a calm, intelligent look into what the next year might hold. It presents itself as foresight—educated guesses arranged into a coherent picture. But sometimes a picture does more than guess. Sometimes it tells you what is already being assumed.

The 2026 cover is one of those moments.

At first glance it’s familiar: conflict iconography, finance, technology, medicine, climate. We’ve seen these motifs before. Look again, though, and something shifts. The question the cover seems to ask is not “What if?” but “How will we live with this?”

That change in tone is subtle, but it matters.

I read this cover using two analytic lenses I’ve been refining for some time. I won’t lay out the mechanics here. Think of them simply as ways of distinguishing genuine uncertainty from quiet expectation, and reaction from consolidation. They are less about who causes events and more about how systems behave before and after them.

Seen through those lenses, the 2026 cover stops feeling like a weather report and starts feeling like a map.

Notice what the imagery does not debate. War is not presented as a risk to be avoided but as an ambient condition—missiles, grey-zone conflict, permanent tension. The implication is not a single decisive war, but a year of sustained escalation: higher defence spending treated as unavoidable, conflicts managed rather than resolved, and the normalisation of confrontation across domains that are difficult to de-escalate.

Medical intervention appears not as emergency but as infrastructure. The signal here is not another crisis, but expansion: wider pharmaceutical adoption, looser thresholds for treatment, and the framing of biochemical intervention as a routine solution to social and economic problems rather than a last resort.

Financial stress is framed as discipline. Bond markets are not shown as volatile or capricious, but as enforcing reality. The implication is that fiscal constraint will be presented as external necessity rather than political choice, with austerity-like outcomes justified as “what markets demand,” even where alternatives exist.

Artificial intelligence is depicted as unavoidable—fragile perhaps, even hollow in places, but still something that must be built. The expectation being set is continued capital expenditure, continued integration into critical systems, and limited tolerance for pause or restraint, even as doubts about robustness quietly grow.

Climate goals linger in the background, rhetorically intact yet practically deferred. The signal here is not denial, but postponement: targets maintained in language while policy and capital are redirected elsewhere, with slippage framed as realism rather than failure.

None of these themes is radical on its own. What is striking is their coherence. Together they describe a future that is already settled in outline. The cover doesn’t invite us to imagine alternatives; it invites us to accept constraints.

This is where the distinction between prediction and normalization becomes important. Predictions describe possibilities. Normalizations describe conditions. The former keep the future open. The latter quietly close it.

When influential institutions present a future as a set of givens, they do more than inform. They prepare. They pre-authorize explanations and narrow the range of responses that will later feel reasonable. When shocks arrive—and they always do—they land on ground already framed.

You can see this in how readily the cover supplies justifications in advance. Militarization is treated as realism. Pharmaceutical expansion becomes necessity. Market discipline replaces political choice. AI build-out is framed as destiny. By the time events unfold, the reasons are already waiting.

That doesn’t require secret coordination or hidden plans. It requires something simpler: shared expectations among powerful actors about what the world is becoming. Once those expectations harden, behavior follows. Budgets align. Narratives converge. Reversal becomes costly, then unthinkable.

So what does this suggest about 2026?

It suggests a year in which escalation is treated as normal rather than exceptional, in which technological and biomedical interventions expand by default, in which financial pressure is used to justify decisions that would once have been debated openly, and in which long-term commitments are made early, narrowing the space for democratic reconsideration later.

Whether those outcomes are good or bad is not the point here. The point is that they are being framed as inevitable.

That framing deserves attention, because it changes how surprise works. When the future has already been rehearsed, events no longer feel shocking. They feel confirmatory. The story was ready.

Forecasts are often read for what they say about tomorrow. Sometimes they tell you more about today—about what influential systems already expect, and therefore what they are quietly preparing to manage rather than prevent.

Read that way, the 2026 cover doesn’t feel like a question posed to the future. It feels like an answer delivered in advance.

And once you notice that, a different question presents itself, one that will matter far more than any single prediction next year.

Are we being shown what might happen, or what has already been assumed will?