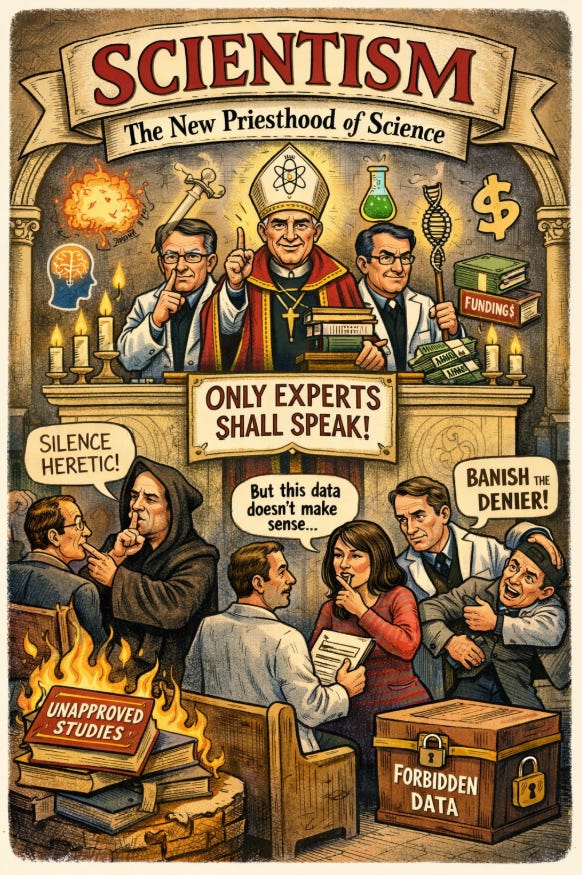

Scientism: The Problem of Unapproved Opinions

How a New Priesthood Replaced Inquiry with Authority

There is a quietly enforced rule in modern culture that is rarely stated outright but constantly applied: you are not allowed to have an opinion unless you are certified to hold it. You may repeat what “experts” say, you may cite institutions, you may defer to credentials, but you are not permitted to reason publicly from first principles unless you belong to the approved class. The moment you do, the response is not engagement but dismissal. “You’re not qualified.” “You’re not a scientist.” “You’re not an expert.” The idea being that truth is not something that can be seen, tested, or reasoned about by an ordinary mind. It must be handed down.

This is a relatively new arrangement in human history, and it is deeply unnatural. For most of our existence, knowledge was something people encountered directly. You observed the seasons, the stars, the land, the body, the consequences of actions. You noticed patterns. You tested claims against what could be seen. You corrected error when it failed. Authority did not determine truth. Reality did.

What we now call “science” was born from that posture. It was never meant to be a priesthood. It was a method: observe, hypothesize, test, revise. Its power came precisely from the fact that no one was supposed to be immune from correction. A claim did not become true because the right person said it. It became true because it survived contact with the world.

Somewhere along the way, that relationship inverted.

Today, the phrase “trust the science” is not a defense of inquiry. It is the opposite. It is a demand for submission to consensus. It says, in effect, that knowledge is no longer something that can be approached by reasoned observation, but something that must be accepted because a recognized authority has spoken. The public is told not merely that experts know more, which is often true, but that non-experts are not even permitted to question the framework. Curiosity itself is treated as transgression.

This is where the cult of expertise begins to resemble theology rather than science.

Peer review, which is supposed to function as a quality filter, increasingly operates as a gatekeeping mechanism. In theory, it tests claims against evidence and methodology. In practice, it often enforces conformity to prevailing models, assumptions, and political boundaries. If a result threatens institutional narratives, funding structures, reputations, or regulatory priorities, it is less likely to be published regardless of its merits. If it aligns with them, its weaknesses are more easily overlooked. What emerges is not the best description of reality, but the most socially acceptable one.

History is not kind to this arrangement.

Medical journals once endorsed bloodletting. Nutritional authorities assured the public that sugar was harmless and fat was the enemy. Pharmaceutical companies produced peer-reviewed studies minimizing addiction risks while entire populations were being quietly poisoned. Financial “experts” certified instruments as safe until the moment they collapsed the global economy. Environmental models, psychological frameworks, epidemiological projections, economic forecasts, cosmological theories—again and again we are told that “the science is settled,” only to watch it be revised, contradicted, or quietly abandoned a decade later.

This is not an indictment of inquiry. It is an indictment of institutionalized certainty.

The uncomfortable truth is that much of what passes for scientific authority is entangled with incentives that have nothing to do with truth. Funding, career advancement, publication access, regulatory capture, political alignment, and reputational risk all exert pressure on what can be said and what cannot. Over time, entire fields become self-referential. The same assumptions are cited by the same journals, funded by the same bodies, reviewed by the same circles, until the distinction between evidence and consensus erodes. What remains is not discovery, but maintenance of the model.

This is why the demand that only “experts” may speak is so dangerous. It does not protect knowledge. It protects power structures built around knowledge.

A person does not need a credential to notice when a model fails to match observation. You do not need a doctorate to see that policies justified by “the science” are producing outcomes opposite to what was promised. You do not need institutional approval to recognize when data is being selectively framed, when uncertainty is being masked as certainty, or when dissent is being reclassified as irresponsibility. The capacity to observe reality and reason about it is not the property of a professional class. It is a human faculty.

The phrase “unapproved opinion” reveals the real issue. It is not that some ideas are wrong. Many are. It is that certain conclusions are not allowed to be reached publicly, regardless of how carefully they are reasoned. The boundary is not epistemic. It is political. Once an opinion threatens an economic model, a regulatory regime, or a narrative of authority, it is no longer evaluated on its coherence. It is simply labeled dangerous.

This is how inquiry dies without anyone noticing.

True science does not require obedience. It requires exposure. A claim that cannot withstand open questioning is not scientific. A theory that depends on silencing dissent is not robust. A consensus that must be protected from ordinary reasoning is not knowledge. It is doctrine.

None of this means that every challenge is correct or that expertise is meaningless. Skill, experience, and deep study matter. But expertise is meant to inform reasoning, not replace it. The moment credentials become a substitute for evidence, the method has been inverted. We no longer ask, “Is this true?” We ask, “Who said it?”

That is not science. It is hierarchy.

The deeper issue is not fraud, though fraud is common enough. It is structural distortion. When institutions reward alignment over accuracy, when careers depend on not noticing certain patterns, when publication depends on not asking certain questions, the entire knowledge system drifts away from reality. And when the public is told that it is illegitimate to think independently about what it can plainly observe, the final safeguard against that drift is removed.

An unapproved opinion is not dangerous because it is wrong. It is dangerous because it is uncontrolled.

Truth does not require permission. Law does not bend to authority. Coherence is not established by vote. A claim is either consistent with reality or it is not. No number of credentials can change that.

The real problem is not that non-experts have opinions. It is that modern systems have forgotten what science was meant to be: not a class, not a credential, not a gate, but a disciplined way of seeing what is actually there.