The Priestly Schism and the DNA of the Cohanim

For much of history, the priesthood of ancient Israel has been imagined as a single, continuous institution, passed cleanly from father to son and preserved intact across centuries. The modern genetic evidence complicates that picture. So do the earliest internal records of priestly authority preserved in the Dead Sea Scrolls. When these two bodies of evidence are placed side by side, a different structure emerges: not a monolithic lineage, but an early division—one that may still be visible in the biological record.

This is not an argument for certainty or for reconstructing lost institutions. It is an attempt to follow the logic of the evidence where it leads.

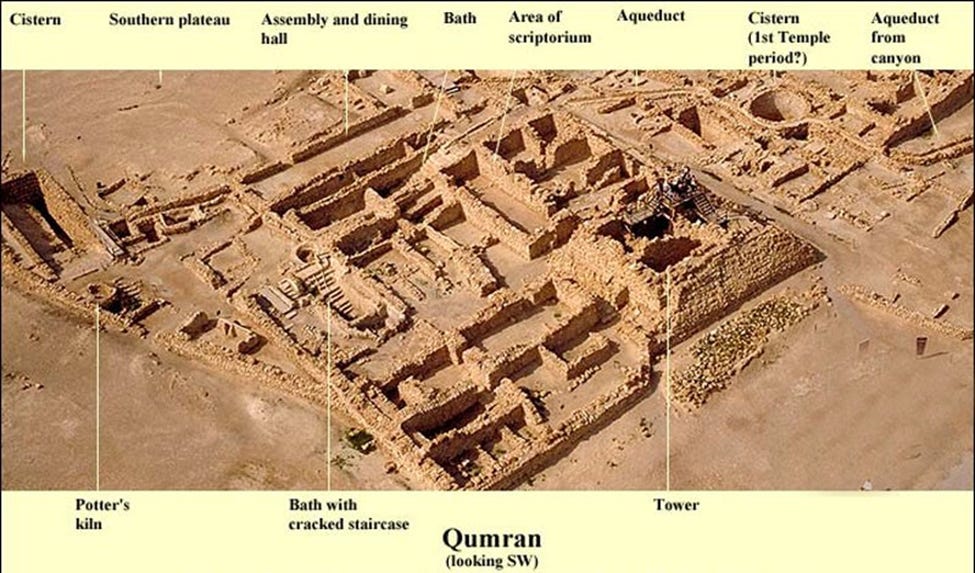

The Dead Sea Scrolls do not represent a single sect or a unified “Qumran doctrine.” As scholars such as Norman Golb have argued, the caves appear to have served as a repository for texts produced in multiple locations and reflecting more than one priestly or legal tradition. What matters here is not authorship by one community, but the content preserved in the corpus itself. Across multiple documents, the scrolls consistently record internal conflict within the priesthood over legitimacy, law, and authority.

At the center of this conflict is the question of rightful priestly rule. The Jerusalem high priesthood is repeatedly depicted as unlawfully constituted. Office had become political. Sacred time had been corrupted through the use of an improper calendar. Ritual was being performed out of lawful order. The texts refer to a “Wicked Priest,” accuse the Temple leadership of defiling the sanctuary, and reject the validity of sacrifices offered under this regime. What mattered, in these writings, was not institutional position but alignment with law. Holiness was defined by obedience to the correct order, not by control of the Temple.

The response described in the scrolls is not reform from within. Certain priestly authorities rejected the Temple establishment outright and located legitimate priestly leadership outside the institutional center. Whether through physical withdrawal, parallel communities, or competing legal traditions, the texts make clear that priestly authority was understood to exist independently of the Jerusalem hierarchy. This represents the earliest surviving documentary evidence of a fracture within the priesthood itself—one grounded in claims of illegitimacy, corrupted office, and violation of sacred law.

The historical record does not preserve genealogies that would allow modern readers to trace these priestly families through subsequent centuries. The destruction of the Temple and the upheavals that followed erased most institutional continuity. What remain are the texts themselves, Josephus’s descriptions of priestly sects living apart from the Temple, and later rabbinic memories of contested appointments and corruption of sacred office. Together, they establish that priestly authority fractured over law, legitimacy, and governance while the Temple still stood.

Separately, modern genetic research into Y-chromosome lineages among men identifying as Cohanim has produced a striking result. Rather than one uniform “Cohen” line, the data reveal several related but distinct male-line branches. These branches are ancient, tracing back to the Near East, and they divide into a dominant cluster found overwhelmingly within Jewish populations and a smaller, more divergent cluster that appears disproportionately in non-Jewish populations. The minor branch is genetically older, more scattered, and far rarer.

Modern Y-chromosome studies also reveal something else: a substantial number of men bearing the name “Cohen” carry no priestly Y-DNA at all. This indicates that priestly status was, at some point, assigned outside biological descent. Historically, this is exactly what would be expected following the Hasmonean seizure of the High Priesthood, when authority became political rather than hereditary. In such a system, some non-priestly lines would acquire priestly status, while some genuine priestly families would lose institutional recognition or withdraw altogether.

This structure raises a simple question: why would a hereditary priestly lineage display precisely this pattern—one major line preserved inside the community, and a smaller, older line found largely outside it?

If the priesthood had remained unified and institutionally continuous, the expectation would be a single dominant lineage concentrated within Jewish populations, amplified over time by communal continuity and endogamy. But if, instead, there was an early rupture—if some priestly families retained institutional authority while others rejected that authority, withdrew from the center, or were displaced by politicized appointments—then a different outcome would follow. The institutional lines would grow and remain visible. The dissident or displaced lines would persist biologically but lose communal status, becoming rare, scattered, and often absorbed into surrounding populations.

That is exactly what the genetic record appears to show.

The congruence here is structural rather than evidentiary. The Dead Sea Scrolls preserve texts that document internal priestly conflict over legitimacy, law, and authority. The Y-DNA record reveals a corresponding bifurcation in priestly lineages: multiple ancient branches, with one dominant and others older, rarer, and geographically diffuse. Neither dataset names individuals or provides a direct chain of descent from antiquity to the present. But the patterns align: a fracture in authority mirrored by a fracture in lineage survival.

This does not require positing a single dissident group as the sole source of the minor genetic branches. The scrolls represent multiple priestly traditions in conflict; Qumran is one documented locus, but not necessarily the only one. What matters is the structural logic. When hereditary authority fractures, lineages follow different demographic paths. Some remain embedded in the institution and multiply. Others separate, lose formal recognition, assimilate, and persist only as biological threads.

The age and dispersion of the minor Cohen Y-lines are consistent with such an early departure. Their presence in non-Jewish populations suggests assimilation long before the medieval or early modern period. Their divergence from the dominant priestly clusters suggests separation near the origins of the priesthood itself rather than a late insertion. In this sense, the genetics do not contradict the historical record; they appear to preserve a deeper layer of it.

This is not proof. No genetic test can identify a specific ancient priestly faction or attach a modern lineage to a named group in the scrolls. What can be said is narrower and more disciplined: two independent records—one textual, one biological—describe the same underlying structure. The priesthood was not monolithic. It fractured over legitimacy and law. Some lines remained within the institutional center and shaped later Jewish history. Others separated early, lost institutional identity, and continued only as unmarked biological descent.

Seen this way, the Cohanim DNA projects do more than confirm tradition. They quietly echo an older conflict embedded in the very origins of priestly authority. What survives today may not be a single lineage, but the long biological shadow of a division that once split the priesthood itself.

Footnote

Norman Golb, Who Wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls? (Scribner, 1995), argues that the scrolls represent a broader Jerusalem library reflecting multiple traditions rather than a single sectarian community at Qumran. For recent genetic analysis of priestly lineages, see Joshua Lipson et al., “Revisiting the lineages of the Cohanim using data from next-generation sequencing,” bioRxiv preprint (2025), which documents multiple ancient Cohen Y-chromosome branches rather than a single uniform lineage.